Author: Simon Varwell

Introducing student engagement

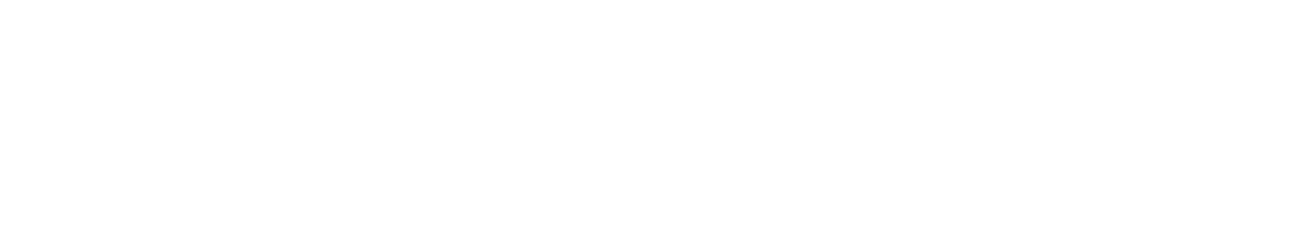

Involving students in shaping the learning experience is woven deeply into quality processes, governance structures and leadership cultures in higher education. Within that, the idea of students as partners and co-creators features strongly.

At a European level, the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area sets out that “[i]nstitutions should ensure that the programmes are delivered in a way that encourages students to take an active role in creating the learning process.” (European Network for Quality Assurance et al 2015, p12)

The United Kingdom’s Quality Code for Higher Education talks about partnership between staff and students as “a mature relationship based on mutual respect between students and staff” (UKSCQA 2013, p2). It further advises that “all staff and students share responsibility for maintaining and developing a culture of student engagement, and as such they will require access to support and guidance on their formal and informal roles and responsibilities around student engagement.” (ibid p6)

In Scotland, a pioneering approach to student engagement is manifested in a sector-agreed Student Engagement Framework, Student Partnership Agreements, and a national development agency for student engagement (sparqs).

Key to all this is the strong role of formalised student representative organisations within institutions, often called students’ unions or students’ associations. Such bodies represent students’ views at various levels of the institution, drawing together perspectives from the diversity of subject areas and student experiences. Ideally, they are professionally resourced to ensure a coherent and informed contribution by senior student leaders.

The views given by students and students’ unions need, of course, to be in keeping with the spirit of partnership. This means a right to be heard, but also a responsibility to give ideas and suggestions that staff can realistically engage with.

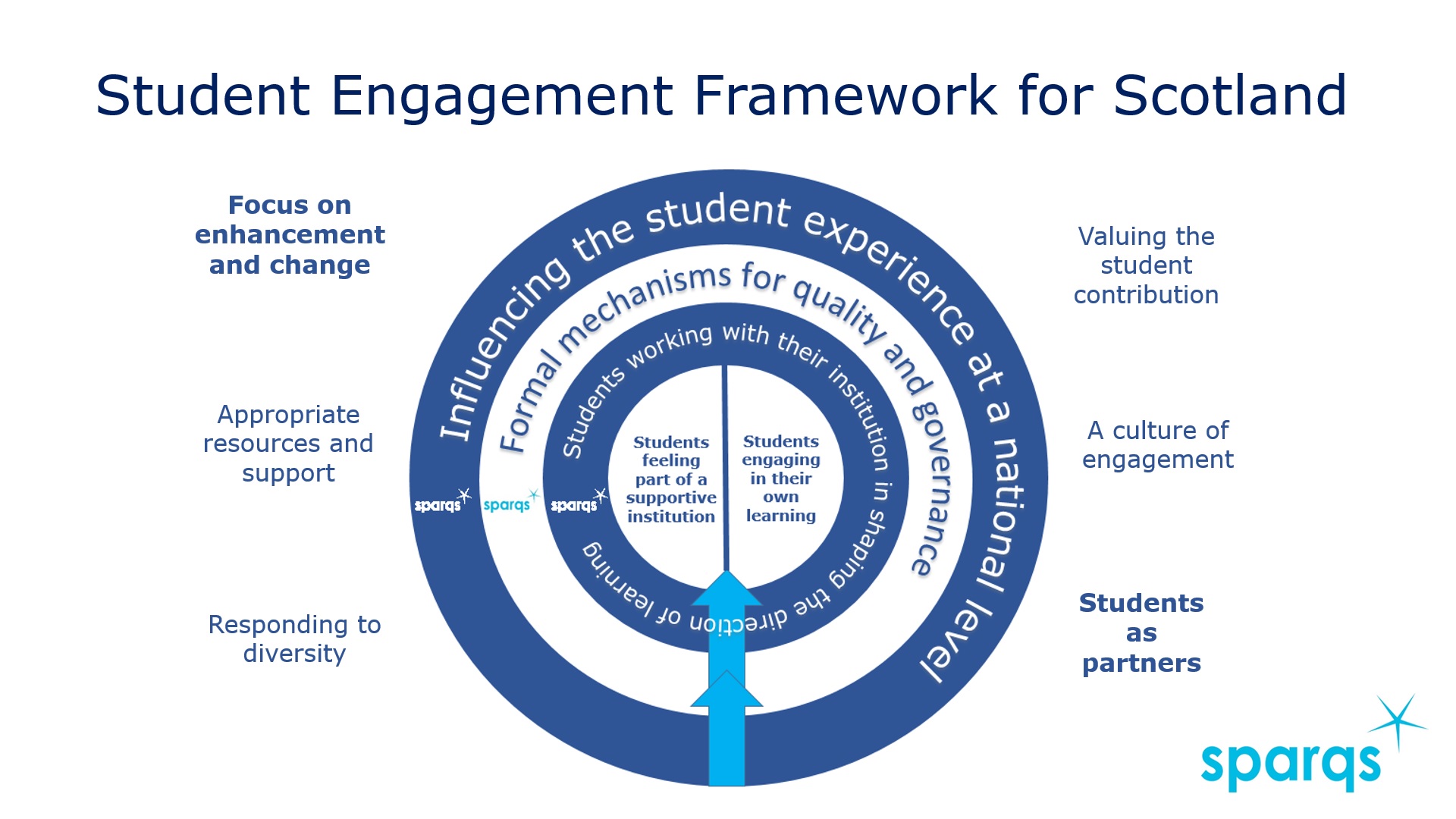

In sparqs’ course rep training, reps are introduced to the “ABCD of Effective Feedback” which they are encouraged to adopt in their formal and informal work with staff such as in course committees, programme boards, student-staff liaison committees or their equivalents:

• Accurate feedback avoids sweeping generalisations and over-emotional language about the learning experience, offering specific comments that are based on evidence.

• Balanced feedback does not just criticise the negative but praises the positive too. This builds good relationships as well as helping staff to identify their successes.

• Constructive feedback moves on from identifying problems to proposing solutions. This allows staff and students to work together on enhancement.

• Depersonalised or diplomatic feedback “plays the ball, not the player” by talking about the impact on learning and not the perceived quality of the teacher.

You may be well placed as an educational developer to help staff and students to generate an agreed standard for communication for student feedback. Outputs could then be incorporated into induction information and training for students, course reps, and teaching staff.

Student engagement in the literature

The idea of students engaging in quality is also explored by an increasing body of academic literature, including wide-ranging literature reviews (Trowler 2010, Lester 2013, Healey et al 2014, Mercer-Mapstone et al 2017). Indeed, there are entire journals devoted to publishing research and case studies on student engagement (such as the Student Engagement in Higher Education Journal, the Journal of Educational Innovation, Partnership and Change and the International Journal for Students as Partners).

Within this literature, there is considerable focus on the types of roles students might have – or be assumed by staff to have – when engaging. For instance, there are five roles identified by Dollinger and Mercer-Mapstone (2018) of consumer, producer, co-creator, partner and change agent.

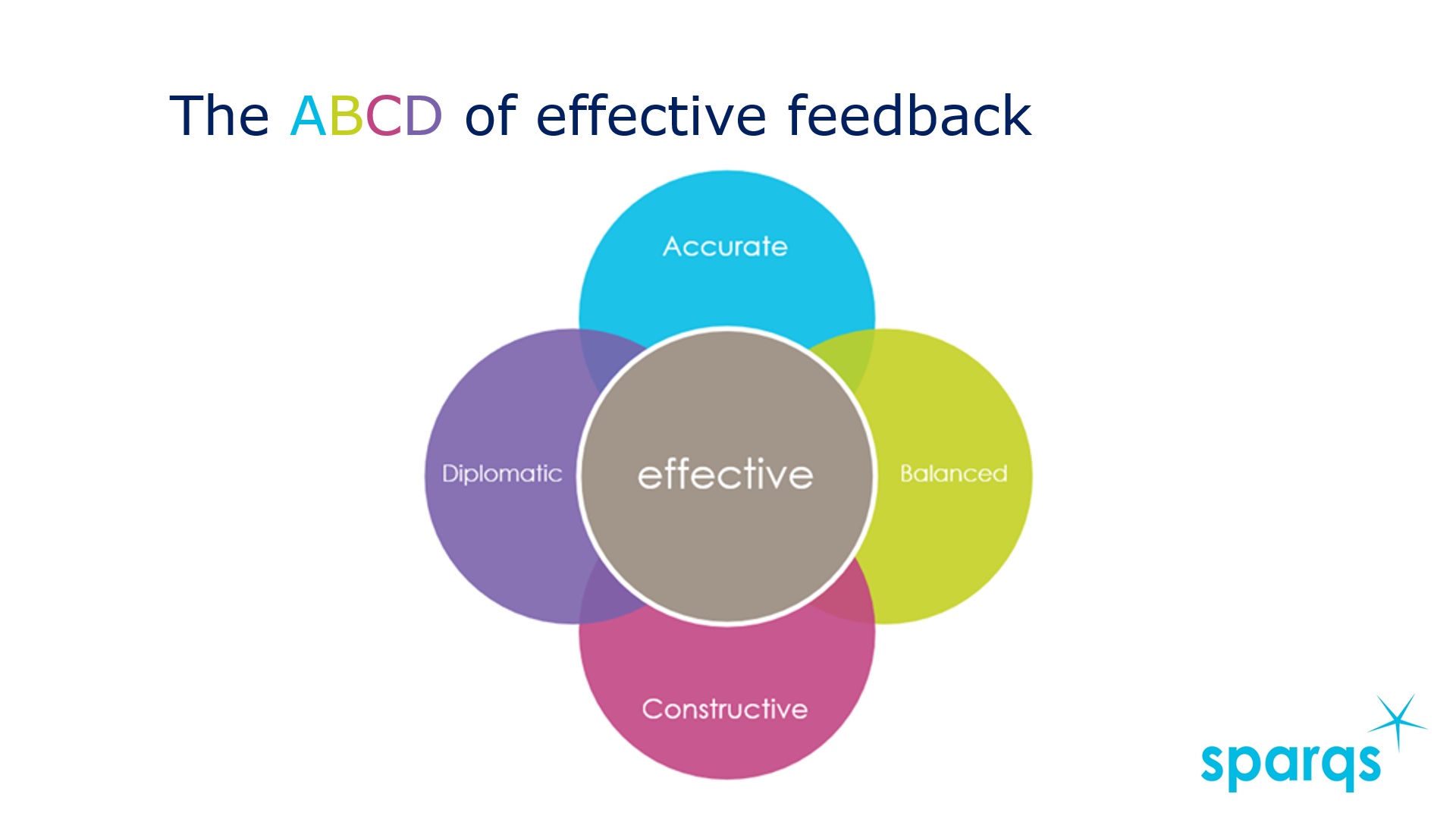

Meanwhile a classic of stakeholder engagement literature is Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation, where eight approaches are explored, including levels both below and above partnership (Arnstein, 1969). Arnstein's descriptions of citizen involvement at each level offer the chance to benchmark and reflect on student engagement, and assess whether partnership is truly being achieved. For instance, two common tools of student engagement are surveys and student places on committees. Yet Arnstein would probably categorize those as only consultation and placation respectively.

Bovill and Bulley have adapted Arnstein’s ladder specifically to explore student engagement in curriculum design (Bovill and Bulley 2011, p. 180).

A student partnership staircase

All these tools are useful for benchmarking, reflection and development. However, to provide a simple and practical way of beginning to think about student roles in quality, sparqs has developed a Student Partnership Staircase.

This offers four possible roles for students, all of which have an important place in quality enhancement. While not all students will move up the ladder (or might skip steps as they do so), educational developers are well-placed to help staff reflect on how they can support, develop and respond to each student role to ensure maximum possible participation at each level.

What does this mean for you in your role?

Questions you could consider incorporating into your work with colleagues are listed below under each role.

Information provider

Students can talk about their learning experience through a variety of tools, such as surveys, focus groups, class discussions or emails with staff. Hopefully all students will be able, and expected, to do this.

- Do staff have a clear picture of all the tools of student feedback at their disposal, including formal and informal?

- How can the tools of feedback be mapped to identify risks such as "survey fatigue"?

- Are staff aware of any student feedback strategy the institution and students’ association have in place? And do they understand their role within it?

- How can staff be sure that feedback tools reflect the breadth of the students they work with? This might include different subject areas or levels, particular campuses, or demographic groups who might traditionally be disadvantaged by the engagement process.

- Can staff create a clear link between the feedback they receive from students and their own professional development priorities?

- How do staff respond effectively to students’ feedback and any action taken?

- How can staff build a sense of mutual faith in and ownership of the tools of feedback, in a way that might encourage students into higher levels of the staircase?

Actor

Beyond merely giving views, students can also work with staff to design the feedback tools, facilitate the process, and analyse the outcomes. Course reps, especially where trained and supported appropriately, may be particularly suited to this deeper role.

- Do staff understand the range of students who might be involved in shaping tools of feedback? Are there others beyond course reps?

- How can staff find out students’ views about the best location and tool for gathering feedback?

- To what extent do staff feel that students bring an authenticity in being ambassadors for feedback processes?

- Do staff know and understand key roles such as course representative? And have they been involved in working with the students’ union to shape those roles?

- What sort of organisational culture – at course, faculty or institutional level – is most conducive to students being actors? And what can staff do to create and promote that culture?

Expert

Just as staff are experts in their discipline, students are also experts in what it is like to learn the discipline in the context of their own lives, hopes and fears. Experiences might be especially enlightening from students with non-stereotypical or majority profiles.

- How well do staff recognise that all students can be experts in their own learning? How can this be done in a way that complements, not detracts from, the fundamental position of staff as experts?

- How do staff “recognise” a student as an expert? What form does that recognition take?

- Can staff identify types of student voices that they do not hear enough from, and from whom they would therefore value expert views?

- What can staff do to create appropriate spaces in which students can be effective as experts? Are there specific kinds of spaces required for those student experts who might not typically engage?

Partner

Students can work with staff as equals, learning and sharing mutually. Such equal working suggests that the relationship might be well-developed, highly trusting and collaborative, and operating within a framework that explicitly embeds partnership. While all students can potentially work with staff in this way, those in specific roles such as project interns, student members of review teams or senior student officers might be commonly found at this level.

- What is authenticity in dialogue? And what is the role of staff within such a dialogue?

- It’s easy to imagine how students might be constructive in a partnership with staff, but what does that mean for staff?

- Although we aspire for partnership, there is an inherent power dynamic between staff and their students, and between an institution and its students’ association. What can staff do to be conscious of that and mitigate its negative effects?

- How can staff demonstrate their mutual learning from students, in order to build faith in the partnership?

- What kind of students might be partners? Do they have to be in a designated role, or is being a partner accessible to the whole student body?

What can you do now?

While there will be value in exploring these questions with teaching colleagues, students and students associations also have a valuable role to play. You, as an educational developer, should not feel the need to provide all the answers, so you could support staff and students to work in partnership on the issues the above questions raise, and identify actions for all parties.

Some useful first steps in doing this might be:

- Meeting with your students' association to develop a mutual understanding of what each of you do to support the learning experience.

- Looking at whether and how training for students and teaching staff on feedback and engagement aligns or is driven by shared principles.

- Exploring how academic departments can create projects to spark partnership conversations and create outputs.

- Contributing the experience of educational development to overall institutional strategies and policies for engagement, partnership, representation and feedback.

*************************************************************************************************

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.